Not “just” a blocked nose. How mouth breathing is affecting your child’s growth and development.

03/18/2016

Being able to nose breathe is something many individuals take for granted. Not only does most normal breathing takes place through the nasal cavity, nasal breathing is the only physiologically normal breathing pattern seen in humans.

Any obstruction within the nasal cavity can be a source of discomfort and have a significant impact on daily life. Nasal airway obstructions narrow and block the nasal passages and prevent the comfortable flow of air in and out of the nose. A nasal obstruction can occur because of inflammation and swelling of the nasal passages and sinuses (e.g. nasal allergies, sinusitis) or structural abnormalities in the nose (e.g. septum deviation, nasal polyps, enlarged adenoids) (Sinha & Guilleminault, 2010).

Far from “just a blocked nose,” a nasal airway obstruction can disrupt an individual’s ability to breathe, speak, eat, exercise and sleep. Left untreated, nasal airway obstruction is a primary cause of chronic obligate mouth breathing, which has been associated with a deleterious health consequences for children and adults alike (Page & Mahony, 2010).

Mouth breathing is not as innocent as many people may think. Though it is natural to partially breathe through the mouth during speech or to maximise air intake when the physiological demand is increased (e.g. during strenuous activity or exercise), the mouth is not actually intended to participate in normal respiration. The function of the oral cavity, or mouth, primarily revolves around speaking and eating, and breathing when nasal respiratory function is inadequate (Lipworth & White, 2000).

There are a number of potentially serious health consequences associated with mouth breathing. Breathing through the mouth instead of the nose upsets the normal balance between the structure and intended functions of the oral cavity. When left untreated individuals can develop craniofacial growth abnormalities, dental and orthodontic problems, skeletal and postural changes, sleeping difficulties, exacerbation of asthma and various other physiological and social health issues (Page & Mahony, 2010).

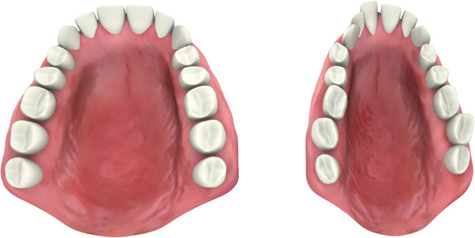

Research shows open mouth breathing can adversely affect the growth and development of the face and jaws by altering the normal positioning of the tongue and lower jaw. When nasal respiratory function is normal, the mouth usually remains closed with the tongue resting in contact with the palate (roof of the mouth). In this position the tongue exerts a lateral force which assists to shape the jaw. The teeth erupt around the tongue producing the normal healthy arch form (Flutter, 2006: Page & Mahony, 2010).

It is not possible to breathe through the mouth and have the tongue rest in the palate simultaneously. To enable breathing the mouth must be open and the tongue drop to the floor. This is problematic, particularly for growing children, as the tongue can no longer provide the “mould” for the upper jaw and teeth to form around (Flutter, 2006). It is quite characteristic of mouth breathers to have a narrow, high arched palate and small underdeveloped top jaw, and subsequently display a narrow face structure, overcrowding of teeth and jaw misalignment (Sinha and Guilleminault, 2010).

During nasal breathing the jaws and mouth tend to naturally remain closed. For chronic mouth breathers though, it is necessary the mouth remains open for extended lengths of time. This causes the downward backward movement of the lower jaw and further contributes to jaw misalignment and long-faced growth patterns. Not surprisingly, mouth breathing is commonly associated with orthodontic abnormalities.

It is quite typical for mouth breathers to tilt their heads backwards to open the airway and maximise air intake. This is because mouth breathing is less efficient than nasal respiration at introducing oxygen into the lungs and bloodstream. Nevertheless, there is no distortion in one part of the body that is not reflected throughout the body. Any head posture where the head is not held level for example, can distort the bones in the skull, including the upper and lower jaws (Flutter, 2006).

Poor head posture and jaw misalignment also affect how the head and spine balance in relation to gravity (Flutter, 2016; Zusko, 2010). When any part of the body is out of alignment with the other parts, there is often a compensating effect throughout the postural chain. In order to maintain the balance of the whole structure, the body must adjust itself. This can involve muscles in the neck, shoulders, back, pelvis, legs and feet. Though often not thought as a health problem, poor posture can place unnecessary wear and tear on joints and over time, be as damaging as an injury (Zusko, 2010).

Dry mouth is a common complaint among chronic mouth breathers. Breathing through the mouth reduces saliva production and increases saliva evaporation. Not only is dry mouth uncomfortable, alterations to salivary patterns can affect an individual’s oral hygiene and dental health. Saliva plays an important role in the self-cleaning of the mouth, neutralising acids and washing away bacteria. With reduced saliva flow, chronic mouth breathers are at increased risk for tooth decay, cavities, gum disease and bad breath (Motta et al., 2011).

Mouth breathing subsequent to nasal airway obstruction is a primary cause of sleep apnoea (pauses in breathing during sleep) (Jefferson, 2010). During open mouthed breathing the lower jaw drops and reduces the diameter of the pharyngeal airway (throat). The airway becomes either partially or completely obstructed and causes individuals to either intermittently or repeatedly briefly stop breathing during sleep. Each time airflow is blocked the brain is deprived of oxygen. Lack of oxygen triggers the brain to arouse the individual so they can resume breathing. Sleep can be interrupted many times each night

Sleep disturbance is common among chronic mouth breathers. Mouth breathing is less efficient than nasal respiration at introducing oxygen into the lungs and bloodstream (Jefferson, 2010). This affects sleep because low blood oxygen concentrations cause the brain to remain in a more aroused state. Being more aroused interferes with the normal sleep cycle. Individuals tend to remain in light sleep for longer periods and be deprived of deep, restorative sleep.

Abnormal facial and dental development can also contribute to poor sleep attainment by making breathing more difficult while laying down. Irritation from drying of the oral mucosa and night sweating associated with the increased effort required to breathe and maintain blood oxygen levels, are additional reasons individuals experience sleep disturbance (Sinha & Guilleminault, 2010).

The importance of sleep to physical and psychological health cannot be overestimated. Sleep is vital for growth and development. For children, research has shown sleep to be linked to growth, development, academic performance, concentration and behavioural problems (Jefferson, 2010).

Nasal airway obstruction and mouth breathing can be very dangerous for individuals with asthma. When breathing through the mouth air is not warmed, humidified or filtered nearly as effectively as when air is breathed in through the nose. Therefore the risk for air which is cold, dry or which contains irritants, pollutants or allergens, entering the lungs is increased. By allowing cold, dry and/or unfiltered air to enter the lungs more easily, mouth breathing increases the risk individuals (with asthma) will have poor asthma control and experience asthma attacks (Lipworth & White, 2000).

Nasal airway obstruction is far from “just a blocked nose.” Nasal breathing is the only physiologically normal breathing pattern seen in humans. Therefore ensuring adequate nasal respiratory function is maintained is very important to health.

Mouth breathing is not an acceptable substitute for nasal breathing. Mouth breathing is associated with numerous deleterious health consequences for adults and children alike. Being aware of the signs and symptoms of nasal airway obstruction and mouth breathing is necessary to enable early intervention and ensure optimal management. Re-establishing nasal breathing is particularly relevant for children as left untreated, mouth breathing can significantly impact growth and development.

Some potential signs of mouth breathing:

– Nasal congestion (“blocked” nose)

– Intermittent or constant open mouthed breathing

– Noisy, visible breathing (physiologically normal breathing is through the nose, silent, smooth and almost invisible)

– Snoring

– Frequent night waking

– Dry mouth (often individual’s report needing to keep a glass of water by the bedside)

– Dry, cracked lips

– Night sweating

– Daytime fatigue

– Behavioural issues (in children)

– Long, narrow face

– Dental or orthodontic issues

– Head posture where head it tilted backwards

– Bad breath

– Poor asthma control

If you are a chronic mouth breather, you are not alone. Recovery of upper airway function and nasal breathing can be achieved with the right professional help!

At the Australian Allergy Centre our allergy doctors are skilled in the diagnosis and management of nasal airway obstruction. All consultations with our doctors are Medicarerebatable. Allergy testing for airborne allergens commonly associated with nasal allergies, and rhinomanometry to assess upper respiratory function, isMedicare rebatable. For more information or to book an appointment, call us today on 1300 MY ALLERGY.

Reference List:

Flutter, J. 2006. The negative effect of mouth breathing o the body and development of the child. International Journal of Orthodontics 17, 2: 31-37. Accessed March 17, 2016: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16881376

Jefferson, Y. 2010. Mouth breathing: adverse effects on facial growth, health, academics and behaviour. General dentistry. Accessed March 15, 2016: http://www.jeffersondental.com/assets/docs/mouthBreathing.pdf

Lipworth, B. and White, P. 2000. Allergic inflammation in the unified airway: start with the nose. Thorax 55, 10: 878-881. Accessed March 3, 2016: http://thorax.bmj.com/content/55/10/878.full.pdf+html

Motta, L., Bachiega, J., Guedes, C., Laranja, L. and Bussadori, S. 2011. Association between halitosis and mouth breathing in children.Clinics 66, 6: 939-942. Accessed March 17, 2016: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3129960/pdf/cln-66-06-939.pdf

Page, D. and Mahony, D. 2010. The airway, breathing and orthodontics. Todays FDA 22, 2: 43-47. Accessed March 17, 2016:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20443530

Sinha, D. and Guilleminault, C. 2010. Sleep disordered breathing in children. Indian Journal of Medical Research 131, 1: 311-320. Accessed March 17, 2016: http://icmr.nic.in/ijmr/2010/february/0221.pdf

Zusko, E. 2010. Posture and Dental Health. Temporomandibular Joint Disorder Effective Diagnosis. Accessed March 17, 2016:http://www.tmjorthocentre.com/index.php/conditions-of-tmd/posture